How Airline Ticket Prices Fell 50 Percent in 30 Years (And Why Nobody Noticed)

Thank deregulation, competition, the internet, and fees. Yes, thank fees.

There are many sad stories to tell about the U.S. economy, but here's some good news for everybody, from radical capitalists to consumer advocates: The incredible falling price of flying

Frank Sinatra's "Come Fly With Me" was the best-selling album in the United States for five weeks in 1958, but the irony of its popularity (or, perhaps, the source of its aspirational appeal) is that practically none of us could take up the offer to "glide, starry-eyed" on an aircraft with anybody in those days. More than 80 percent of the country had never once been on an airplane. There was a simple reason. Flying was absurdly expensive.

And there was simple reason why flying was absurdly expensive. That was the law.

There are many sad stories to tell about the U.S. economy in the last 30 years, but here's a happy story for everybody (except the airlines), from radical capitalists to the most liberal consumer advocates. Getting government out of the business of regulating the skies has led to a remarkable collapse in airline prices.

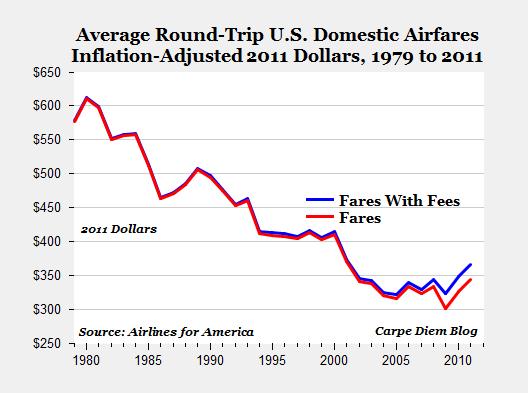

Airfares have fallen by about 50 percent since 1978 ...

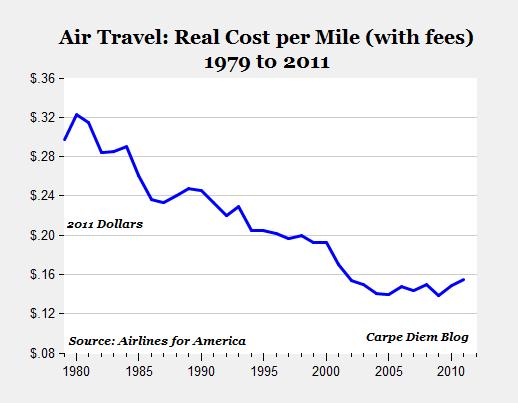

... and, even after you include the recent uptick in fees, the per-mile cost of flying has also been chopped in half.

A happy story for consumers isn't necessarily a happy story for the airline industry, which bled an astounding $51 billion between 2001 and 2011 and lost money in every other year since 1981.

So, why have the last three decades been so good for flyers? And why don't we appreciate it?

THE DEMOCRATIZATION OF THE AIR

If you want a two-word answer to why airfares have dropped so much since the 1970s, it's this: Deregulation worked.

Before 1978, the airlines played by Washington's rules. The government determined whether a new airline could fly to a certain city, charge a certain price, or even exist in the first place. With limited competition, airlines were guaranteed a profit, and they lavished flyers with expensive services paid with expensive airfares. The silver and cloth came at a predictable price: The vast majority of Americans couldn't afford to fly, at all.

With prices skyrocketing during the energy crisis of the 1970s, an all-star team of senators and economists decided that Washington should get out of the business of coddling the airlines. Let's hear from a young former aide to Sen. Ted Kennedy named Stephen Breyer (oh, yeah, that Stephen Breyer) reviewing the free market case for letting airlines fly solo:

In California and Texas, where fares were unregulated, they were much lower. The San Francisco-Los Angeles fare was about half that on the comparable, regulated Boston-Washington route. And an intra-Texas airline boasted that the farmers who used to drive across the state could fly for even less money -- and it would carry any chicken coops for free.

Three decades later, the lesson from Texas -- if you deregulate the skies, ticket prices will fall -- has been applied across the country. The democratization of the air is obvious enough from the frenetic bustle of every major U.S. airport. But the stats are mind-blowing, as well.

-- In 1965, no more than 20 percent of Americans had ever flown in an airplane. By 2000, 50 percent of the country took at least one round-trip flight a year. The average was two round-trip tickets.

-- The number of air passengers tripled between the 1970s and 2011.

-- In 1974, it was illegal for an airline to charge less than $1,442 in inflation-adjusted dollars for a flight between New York City and Los Angeles. On Kayak, just now, I found one for $278.

Why did deregulation create such dramatically falling prices? "Flying is neither a life necessity like tuition, milk, or medicine, nor is it addictive, like alcohol or drugs," said John Heimlich, vice president and chief economist at Airlines for America. "When you have intense competition for a product that is price sensitive, you have falling prices."

MACHINE vs. MACHINE: THE PRICE WARS

In the showdown between airlines and flyers, both sides wield a formidable weapon. Airlines use computers to move prices. We use computers to find the lowest price. It's like a multi-billion-dollar game of cat and mouse played out between competing machines -- with William Shatner caught the middle.

When the doors of an airplane close, each empty seat is lost money. So the price of a ticket should fall as we approach takeoff, right? Wrong. As you know, airfares rise in the final hours. This is because last-minute flyers tend to be desperate people (they'll pay anything) or businesspeople expensing to their companies (they'll pay anything). So airlines have to design a system that fulfills the following goals: Sell as many seats as possible, sell them a profit, but also leave some empty for desperate travelers.

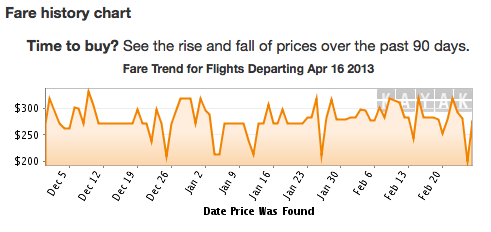

That explains why the life-cycle of an airfare resembles a roller coaster. A seat is a seat is a seat, you might say. But a ticket sold three months out isn't worth the same to the buyer as a ticket sold the same day. So you can pay $200 to fly to Chicago and sit next to somebody who paid $600.

Complex and closely guarded technology owned by the airlines create a market of jiggling price points with, not just thousands of airfares, but millions of airfares, as Charles Fishman reports:

Continental launches about 2,000 flights every day. Each flight has between 10 and 20 prices. Continental starts booking flights 330 days in advance, and every flying day is different from every other flying day. Monday is a different kind of day than Tuesday; the Wednesday before Thanksgiving is different from the Wednesday before that. At any given moment, Jim Compton and Continental may have nearly 7 million prices in the market.

While airlines worked to make low prices impossible to pin down, the internet made finding the lowest price easier than ever. In the late 1990s, Expedia and Priceline launched technologies that trawled the Web for flights and organized them by price. The airlines' magical formula was transformed into a column of bargains.

What this has done to airfares is obvious: Transparency accelerated the competition for the lowest prices. Airlines still compete on schedules, routes, and service, just like the old days, but now that flying has moved mass market, "airfare moves market share," said Henry H. Harteveldt, a travel industry analyst with Atmosphere Research. "It's allowed cheap airlines like Southwest and Jet Blue and Spirit to enter the market and grow." Just as regulation came at a price (fewer flyers), deregulation and low airfares have created their own complications: spartan service, bankrupt airlines, and a brave new world of fees.

THE RISE OF FEES (AND THE CASE FOR LOVING THEM)

Flyers hate fees. But we might learn to love them if we thought of them as savings.

After deregulation, airlines wanted to guard their slim profits in an online world of transparent prices. One solution was to offer cheap basic fares and tack on fees later for amenities that most customers would demand. Today, airline fees have grown into a $6 billion side-pot -- quadrupling in just the last five years. There are now fees for bags, WiFi, food, headsets, unaccompanied minors, the emergency row, and practically everything that cannot be simply described as "one adult sitting with a back-pack in one middle seat."

Why do we hate fees if they keep basic prices low? Because we're Americans, Heimlich said: "It's the American way to want a product approaching first-class for a price approaching zero." But cultural selfishness doesn't explain all of it. Bargain-hunters experience a dopamine rush (literally) when they find great prices. The drip-drip of additional fees mutes the joy of finding a great price. They kill our buzz.

IF FLYING IS SO CHEAP, WHY DO WE THINK IT'S EXPENSIVE?

When US Airways and American Airlines announced their mega-merger this year, it set off national hysterics, as flyers claimed the new behemoth would painfully raise prices. The reaction seemed unaware that consumers have enjoyed an amazing (and unsustainable) three decades in cheap flying while the price of fuel, which accounts for more than a third of airfare costs, has gone up 260 percent since the turn of the century.

Between falling prices, 9/11, and fuel inflation, there have been 47 airline bankruptcies since 2001. Some companies died. Others merged. Others survived with leaner contracts. Through attrition and consolidation, a less crowded marketplace for flying is inevitable.

Why don't we appreciate this heyday in bargain flying? The first, and obvious, answer is that flying through the air in a big machine powered by a scarce resource will always cost a big number, and your average family expends very little energy adjusting big numbers for inflation. If you buy a round-trip ticket from New York to Columbus for $280 every year between 1986 and 2010, would you suddenly realize, after 24 years, that the real price of your ticket had dropped by exactly 50 percent? Probably not. You'd probably think, correctly, "I guess flying to Ohio costs $280."

The second, and less obvious, reason why we don't recognize the amazing fall in ticket prices is that average consumers don't know what a plane ticket "should" cost. Some prices, we know, as if by heart. Parents know the price of socks, teenagers know the price of Cheetos, and college kids know the price of PBR. These numbers hardly change. Their constancy anchors an expectation. But quick, what's *the price* of flying to Los Angeles? You have no idea. It could be $300 or $700, depending on the route, the time of day, the number of seats left, the number of days notice, and so on.

Essentially, Americans are expert shoppers, not mathematicians. Don't ask us to divine the true cost of something, or to adjust for inflation. We only know how to click the cheapest price. And, for the airlines, that's precisely the problem.